Misquamicut ruling backs owners

WARWICK — A Superior Court judge has ruled in favor of 21 Misquamicut property owners, finding that the public does not have the right to use the beach adjacent to their homes.

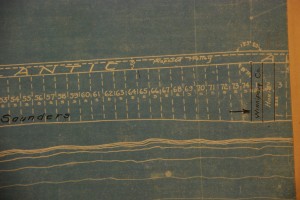

Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Kilmartin filed suit against the property owners in 2012, claiming that the five original owners of land on both sides of Atlantic Avenue, for a 2-mile stretch from east of Misquamicut State Beach to the Weekapaug Breachway, dedicated the beach area of their land to the public for use by all in 1909. The current property owners, the state said, were creating a private and public nuisance by blocking access with fences and harassing beach-goers.

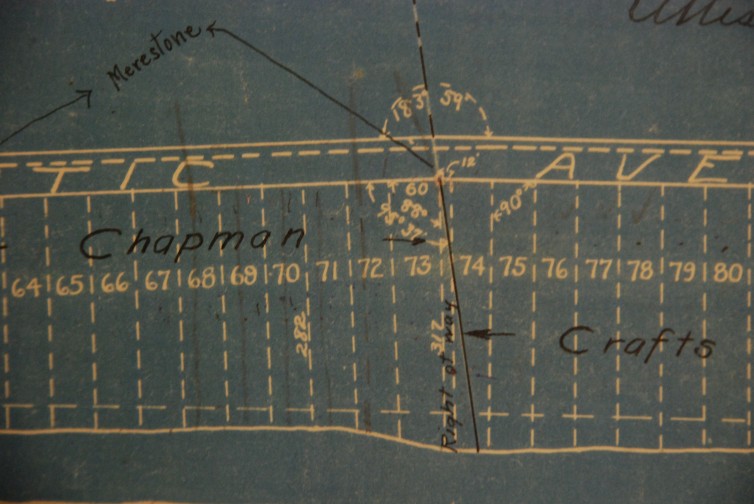

In a 39-page decision released Thursday, Judge Brian Stern ruled that the original owners, when they depicted a subdivision of their property in 1909 on a plat or map, did not intend to dedicate the beach area to the public. The status of the property had been in dispute for decades before the lawsuit was filed. Members of the public insisted that the area was historically available for public use, but the property owners chafed, in some instances erecting fences and calling the police to report beach visitors as trespassing.

The decision does not affect the public’s right to use the beach area below the mean high tide mark, an area preserved for public use by state and federal laws.

On Thursday, William Landry, the lawyer representing the defendants, said his clients “always believed their property was private and it had always been treated as private. My clients are very pleased to have this private property right reaffirmed.”

“It has been an ordeal, many of these people are just normal families that made life decisions to purchase these properties,” he said.

While the case has been described as “a beach access case,” Landry said the case differed greatly from the majority of such cases, which deal with the area below the mean high tide mark. “This was unique in that it was a very fact specific case that involved expert testimony all based on a 1909 plat,” he said.

The property owners, Landry said, bear “no animus toward the public or its right to walk below the mean high tide mark. In fact there are a number of rights of way giving access to that area. My clients never contested or resisted that.”

The judge based his decision on six general findings. Observing that the 1909 plat depicted property owned by at least four property owners who did not sign the plat or the accompanying indenture document recorded in the Westerly land records at the same time as the plat, Stern said the plat could not possibly be used as evidence to support the state’s argument that the beach area was dedicated as open to the public.

“Necessarily, since the signers to the 1909 plat and the indenture did not have the ability to dedicate easement rights over property that did not belong to them, it would have been impossible for the plattors to dedicate an easement over the entire contiguous disputed area they labeled as ‘Beach,’” Stern wrote.

In his second finding, Stern said there was no legal foundation to the state’s argument that most of the disputed beach was dedicated to the public by virtue of the signatures of the five property owners who signed the 1909 plat. State law, Stern said, requires that all of the owners of property join together in dedicating land to the public.

The judge strenuously rejected the state’s argument that the 1909 plat and indenture “clearly and unambiguously” showed an intent to dedicate the beach area to the public, calling the argument “spurious at best.” In this, his third finding, Stern said lines on the plat used to delineate the northern and southern boundaries of the contiguous beach area were different from the lines used to depict streets and roads, other public areas.

“The plattors had no reason to think that their depiction of an area labeled ‘Beach’ on their platted parcel would be construed, either then or one hundred years later, as an incipient dedication,” Stern wrote.

Michael Rubin, assistant attorney general, and Gregory Schultz, special assistant attorney general, had argued that if Stern found the plat unclear or ambiguous, he would have to rely on other evidence and testimony from expert witnesses to make his decision. While Stern wrote in parts of his decision that he did consider the testimony of expert witnesses for both the state and the defendants, he concluded in his fourth finding that the plat and indenture are not ambiguous. “One reasonable interpretation of the 1909 plat and the indenture is that the plattors did not intend to” dedicate the beach as public, he wrote.

The judge’s fifth finding deals with additional evidence, aside from the plat and indenture, submitted by the state. One of the state’s central arguments involved assertions that some of the plaintiffs “magically” changed the deeds for their property based on erroneous surveys that resulted in new property boundaries being depicted to show the beach as private land. Stern called the deeds, surveys, tax assessor plans and communications between state agencies and property owners that had been offered as evidence by the state “superfluous if not exactly irrelevant” in the face of the central question in the case — the intention of the property owners who signed the 1909 plat.

Stern found — as Landry, the lawyer for the plaintiffs had argued — that the original deeds that reserved beach rights for third parties, following the recording of the 1909 plat, reflected possible pre-existing arrangements with third parties but not an outright dedication of the beach area to the public at large. The judge also wrote that he found persuasive evidence and testimony that the plat’s depiction of the northern boundary of the beach, described in the 1909 documents as “line of foot of bank,” showed a geographic feature, not a boundary of the beach or an area for public use.

In his final finding, Stern delves into language used in the indenture. The state said descriptions of the property that described 12 rights of way as running “to the beach” showed that private property in the disputed area stopped at the beach because the beach was public. Stern however, said that in an age prior to the advent of zoning laws, when the plat and indenture were developed, the signers may have had an interest in demonstrating to potential buyers of the land that there was a way for the public to access the beach area in the event that new property owners developed storefronts on the beach or wanted to charge people for using the beach.

In a news release issued Thursday afternoon, Kilmartin said he filed the lawsuit “in part, to bring finality to a longstanding contentious conflict that was dividing beach-front homeowners and those who sought to enjoy the beach area.”

The judge’s decision is being analyzed by Kilmartin and his staff.

“Public access to our waterfront and beaches is a long-held, shared expectation of the people of Rhode Island. We are, after all, the Ocean State. We will carefully review and consider the court’s findings to determine how the state may proceed,” Kilmartin said.

The state and the defendants each submitted 200 exhibits into evidence during an April trial conducted over the course of 11 hearing days. Ten witnesses testified during the trial, which was followed by additional oral arguments in early July.

The lawsuit originally named just seven defendants. Early in the proceedings, over the state’s objection, Stern required the state to provide notice of the suit to neighboring landowners. The number of defendants then grew to 21.

The following is a list of the defendants and defendant intervenors: Joan M. Barbuto, Lynne D. Kaesmann, Susan Brandt, Joann Harrington, Clarence G. Brown, Judith W. Brown, John B. Stellitano, trustee of The John Bruno Stellitano Living Trust; James M. Tobin, Joshua Vocatura, Hattie G. Vocatura Trust, Nicholas P. Jarem, Sandra L. Jarem, Micmays Llc., Joan A. Carr, John C. Maffe Jr., Patricia Jean Shannon, Stephanie E. Immel, Jeanne E. Shannon, Joseph M. Shannon, Dunes Park Inc., Donna Pirie, Margaret Andreo, Jane L. Taylor, David K. McGill, Miriam B. McGill, Timothy F. Shay, Brian P. Shay, Justin T. Shay, and Jeffrey A. Feibelman, Trustee of the 627 Realty Trust.

Will Collette

5539 Post Road

Charlestown RI 02813-1745